During our preparations for the concert at Dokkhuset in May 2018, we had several sessions of combined rehearsal and studio recording. We aimed for doing a recording of the concert and using that for a public release, but wanted to record the preparations too, in case we needed additional (or backup) material. We ended up using a combinations of the live and studio recordings for the upcoming release, so in that respect the strategy worked as planned.

Since we already had a substantial documentation of practical experiments from earlier sessions, we decided to not document these sessions with video and written reflections. One could of course say that the sessions are still documented with audio recordings, although I would characterize these different modes of documentation so differently that they require different treatment and impacts the production and the reflection if very different ways. We as musicians are quite used to working in the studio, used to being recorded, and familiar with the scrutiny that follows from this process. Close miking in an optimal recording environment brings out details that you would not necessarily notice otherwise. The impact of the difference in documentation methods and documentation purpose is the aim of this blog post.

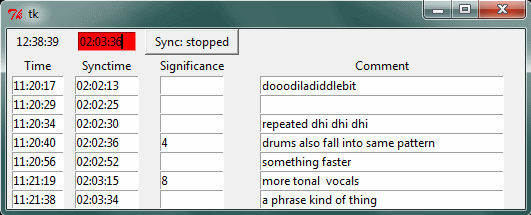

During the practical sessions earlier in this project, we had done what I would call a full video documentation. This consisted of a written session report form (with objectives, listing of participants and takes, reflections during and after the session), a 4-camera video recording of the full session, with reflection interviews after the session, a video digest with highlights of the raw video takes, and a blog post summing up and presenting the results. This recipe was developed as a collaboration between Andreas Bergsland and myself, with Bergsland leading the interviews and taking care of all parts of the video production. A documentation software tool (docmarker) was also developed by me, to aid in marking significant moments in time during sessions, with the purpose of speeding up the process of sifting through the material when editing.

Such an extensive documentation format of course requires substantial resources, but care was taken to try to ensure that the artistic process should not be slowed down by documentation work. We had dedicated personell doing the documentation, for most sessions Bergsland would transparently take care of the video production. The reflective interviews were done after all performing activities were completed, and we also had considerable technical assistance from studio engineers (led by Thomas Henriksen). All this should ensure that any burden of documentation should not impose any hindrance to the workflow of the artistic process being documented.

Still, when we did these final rehearsals in May 2018 without this kind of documentation, I realized that the process and the workflow was much faster. It seems for me like the act of being documented influence the flow of the process in a very significant manner. I relate this to a difference between a pure artistic process, and an artistic research process. I do not propose that what I say here has any form of general validity, but I do recognize it within my own experience from this project and from earlier artistic research projects. It appears to be related to being aware of one’s own intentions on an intellectual level, as opposed to “just doing”. During my doctoral research project “New creative possibilities through improvisational use of compositional techniques, – a new computer instrument for the performing musician” finished in 2008, I also noted this difficulty of doing research on my own process. The being inside while looking from the outside. The intuitive and the analytic. The subjective and the attempt at being objective. During an earlier session in the crossadaptive project, Bergsland asked me right after a take what I had done during that take. I replied that I did exactly what I said I should (before the take). He then noted that it did not sound as if this was what happened, and I needed to check my settings and realized, yes, … I had actually done some adjustments early in the take “just to make it work”.

After this insight in the May sessions, I have discussed this issue with several collagues. Many seem to agree with me that it would be interesting to try to document the moment when an artistic process ignites, the moment when “it happens”. Many also recognize the inevitable slowdown due to an analytical component being introduced into the inner loop of the process. Others would say that I must be doing something wrong if the act of documentation slows me down so much. The way I experience this, the artistic process has several layers, each with it’s own iteration time. Parts of the process iterates on the time scale of years, where reflective insight and slow learning influence the growth of ideas. Other intermediary layers also exist as onion skin layers before we get to the inner loop that is active during performance. Here, the millisecond interactions between impulses and reactions is at the most sensitive to interruptions and distractions. Any kind of small drag at this level impedes the flow and slows down the loop, sometimes to the extent that it will not work, it stops. As if it was a rotating wheel with a self-preserving spin, delicately balancing between friction and flow. On the longer time scales, documentation does not imede the process, but rather it can enrich it. On those time scales I also recognize the accumulation of material, of background research, technical solutions, philosophical perspectives and so on. It may seem like the gunpower to allow something to ignite is collected during those longer loops, while the spark… well that is a fickle and short-lived entity more vulnerable to analytical impact. In quantum physics there are also (as far as I know) particles too small to be observed, where the act of observation collapses a potentiality. Maybe there is a similar uncertainty principle in artistic research?