The liveconvolver has been used in several concerts and sessions in San Diego this spring. I played three concerts with the group Phantom Station ( The Loft , Jan 30th, Feb 27th and Mar 27th), where the first involved the liveconvolver. Then one concert with the band Creatures ( The Loft , April 11th), where the live convolver was used with contact mikes on the drums, and live sampling IR from the vocals. I also played a duo concert with Kjell Nordeson at Bread and Salt April 13th, where the liveconvolver was used with contact mikes on the drums, live sampling IR from my own vocals. Then a duo concert with Kyle Motl at Coaxial in L.A (April 21st), where a combination of crossadaptive modulation and live convolver was used. For the duo with Kyle, I switched between using bass as the IR and vocals as the IR, letting the other instrument play through the convolver. A number of studio sessions was also conducted, with Kjell Nordeson, Kyle Motl, Jordan Morton, Miller Puckette, Mark Dresser, and Steven Leffue. A separate report on the studio sesssion in UCSD Studio A will be published later.

“Phantom Station”, The Loft, SD

This group is based on Butch Morris’ conduction language for improvisation, and the performance typically requires a specific action (specific although it is free and open) to happen on cue from the conductor. I was invited into this ensemble and encouraged to use whatever part of my instrumentarium that I might see fit. Since I had just finished the liveconvoolver plugin, I wanted to try that out. I also figured my live processing techniques would fit easily, in case the liveconvolver did not work so well. Both the live processing and the live convolution instruments was in practice less than optimal for this kind of ensemble playing. Even though the instrumental response can be fast (low latency), the way I normally use these instruments is not for making a musical statements quickly for one second and then suddenly stop again. This leads me to reflect on a quality measure I haven’t really thought of before. For lack of a better word, let’s call it reactive inertia : the possibility to completely change direction on the basis of some external and unexpected signal. This is something else than the audio latency (of the audio processing) and also something else than the user interface latency (like for example, the time it takes the performer to figure out which button to turn to achieve a desired effect). I think it has to do with the sound production process, for example how some effects take time to build up before they are heard as a distinct musical statement, and also the inertia due to interaction between humans and also the signal chain of sound production pre effects (say if you live sample or live process someone, need to get a sample, or need to get some exciter signal). For live interaction instruments, the reactive inertia is then goverened by the time it takes two performers to react to the external stimuli, and their combined efforts to be turned into sound by the technology involved. Much like what an old man once told me at Ocean Beach:

“There’s two things that needs to be ready for you to catch a wave

– You, …and the wave”.

We can of course prepare for sudden shifts in the music, and construct instruments that will be able to produce sudden shifts and fast reactions. Still, the reaction to a completely unexpected or unfamiliar stimuli will be slower than optimal. An acoustic instrument has less of these limitations. For this reason, I switched to using the Marimba Lumina for the remaning two concerts with Phantom Station, to be able to shape immediate short musical statements with more ease.

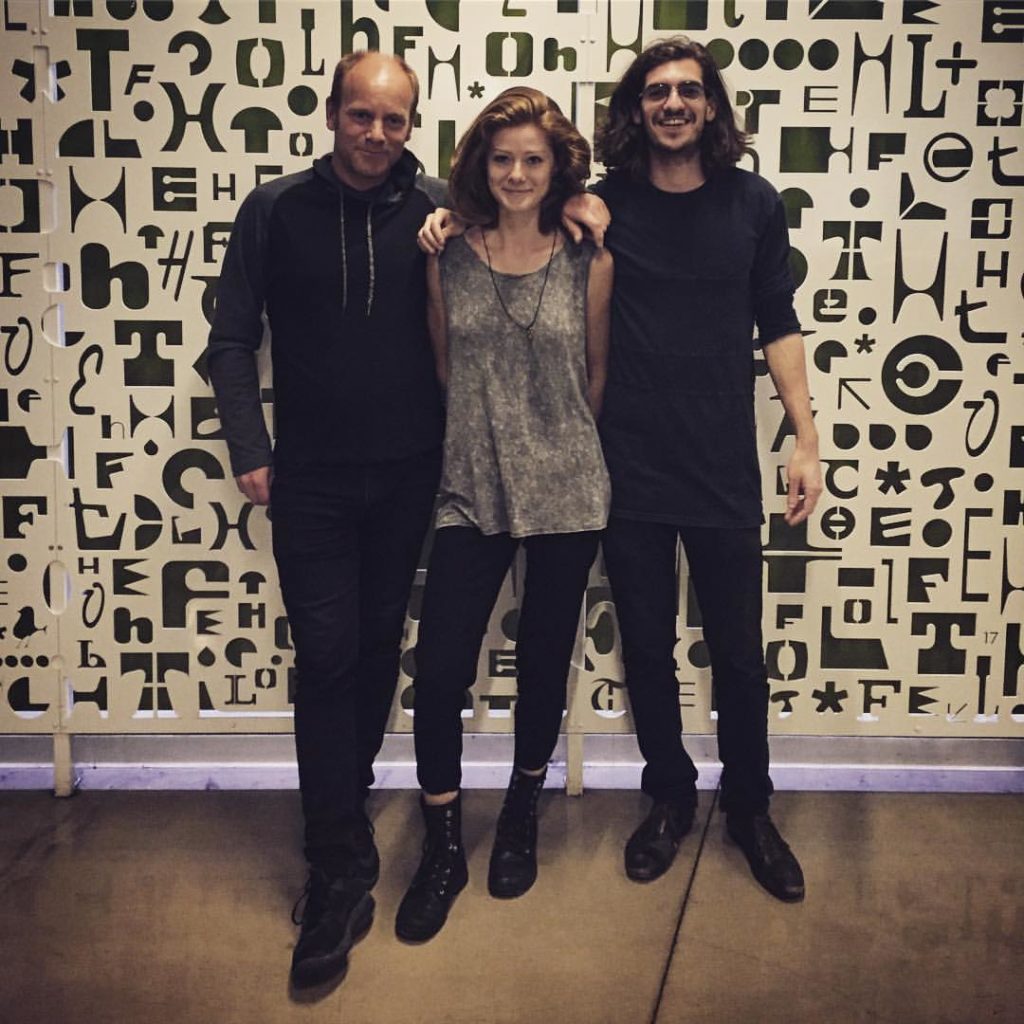

“Creatures”, The Loft, SD

Creatures is the duo of Jordan Morton (double bass, vocals) and Kai Basanta (drums). I had the pleasure of sitting in with them, making it a trio for this concert at The Loft . Creatures have some composed material in the form of songs, and combine this with long improvised stretches. For this concert I got to explore the liveconvolver quite a bit, in addition to the regular live processing and Marimba Lumina. The convolver was used with input from piezo pickups on the drums, convolving with IR live recorded from vocals. Piezo pickups can be very “impulse-like”, especially when used on percussive instruments. The pickups’ response have a generous amount of high frequencies, and a very high dynamic range. Due to the peaky impulse-like nature of the signal, it drives the convolution almost like a sample playback trigger, creating delay patterns on the input sound. Still the convolver output can become sustained and dense, when there is high activity on the triggering input. In the live mix, the result sounds somewhat similar to infinite reverb or “freeze” effects (using a trigger to capture a timbral snippet and holding that sound as long as the trigger is enabled). Here, the capture would be the IR recording, and the trigger to create and sustain the output is the activity on the piezo pickup. The causality and performer interface is very different than that of a freeze effect, but listening to it from the outside, the result is similar. These expressive limitations can be circumvented by changing the miking technique, and working in a more directed way as to what sounds goes into the convolver. Due to the relatively few control parameters, the main thing deciding how the convolver sounds is the input signals. The term causality in this context was used by Miller Puckette when talking about the relationship between performative actions and instrumental reactions.

Creatures at The Loft. A liveconvolver example can be found at 29:00 to 34:00 with Vocal IR, and briefly around 35:30 with IR from double bass.

“Nordeson/Brandtsegg duo”, Bread & Salt, SD

Duo configuration, where Kjell plays drums/perc and vibraphone, and I did live convolution, live processing and Marimba Lumina. My techniques was much like what I used with Creatures . The live convolver setup was also similar, with IR being live sampled from my vocals and the convolver being triggered by piezo pickups on Kjell’s drums. I had the opportunity to work over a longer period of time preparing for this concert together with Kjell. Because if this, we managed to develop a somewhat more nuanced utilization of the convolver techniques. Still, in the live performance situation on a PA, the technical situation made it a bit more difficult to utilize the fine grained control over the process and I felt the sounding result was similar in function to what I did together with Creatures. It works well like this, but there is potential for getting a lot more variation out of this technique.

We used a quadrophonic PA setup for this concert. Due to an error with the front-of-house patching, only 2 of the 4 lines from my electronics was recorded. Due to this fact, the mix is somewhat off balance. The recording also lacks first part of the concert, starting some 25 minutes into it.

“The Gringo and the Desert”, Coaxial, LA

In this duo Kyle Motl plays double bass and I do vocals, live convolution, live processing, and also crossadaptive processing. I did not use the Marimba Lumina in this setting, so some more focus was allowed for the processing. In terms of crossadaptive processing, the utilization of the techniques is a bit more developed in this configuration. We’ve had the opportunity to work over several months, with dedicated rehearsal sessions focusing on separate aspects of the techniques we wanted to explore. As it happpened during the concert, we played one long set and the different techniques was enabled as needed. Parameters that was manually controlled in parts of the set, was then delegated to crossadaptive modulations in other parts of the set. The live convolver was used freely as one out of several active live processing modules/voices. The liveconvolver with vocal IR can be heard for example from 16:25 to 20:10. Here, the IR is recorded from vocals, and the process acts as a vocal “shade” or “pad”, creating long sustained sheets of vocal sound triggeered by the double bass. Then, liveconvolver with bass IR from 20:10 to 23:15, where we switch on to full crossadaptive modulation until the end of the set. We used a complex mapping designed to respond to a variety of expressive changes. Our attitude/approach as performers was not to intellectually focus on controlling specific dimensions but to allow the adaptive processing to naturally follow whatever happened in the music.

Gringo and the Desert at Coaxial DTLA, …yes the backgorund noise is the crickets outside.

Session with Steven Leffue (Apr 28th, May 5th)

I did two rehearsal sessions together with Steven Leffue in April, as preparation for the UCSD Studio A session in May. We worked both on crossadaptive modulations and on live convolution. Especially interesting with Steven is

his own use of adaptive and crossadaptive techniques

. He has developed a setup in PD, where he tracks

transient density

and

amplitude envelope

over different time windows, and also uses

standard deviation

of transient density within these windows. The windowing and statistics he use can act somewhat like a feature we have also discussed in our crossadaptive project: a method of making an analysis “in relation to the normal level” for a given feature. Thus, a way to track relative change. Steven’s Master thesis

“Musical Considerations in Interactive Design for Performance”

relates to this and other issues of adaptive live performance. Notable is also his ICMC paper

“AIIS: An Intelligent Improvisational System”

. His music can be heard at

http://www.stevenleffue.com/music.html

, where the adaptive electronics is featured in “A theory of harmony” and “Futures”.

Our first session was mainly devoted to testing and calibrating the analysis methods towards use on the saxophone. In very broad terms, we notice that the different analysis streams now seem to work relatively similar on different instruments. The main diffferences are related to extraction of tone/noise balance, general brightness, timbral “pressedness” (weight of formants), and to some extent in transient detection and pitch tracking. The reason why the analysis methods now appear more robust is partly due to refinements in their implementation, and partly due to (more) experience in using them as modulators. Listening, experimentation, tweaking, and plainly just a lot of spending-time-with-them, have made for a more intuitive understanding of how each analysis dimension relates to an audio signal.

The second session was spent exploring live convolution between Sax and Vocals. Of particular interest here is the comments from Steven regarding the performative roles of IR recording vs playing the convolver. Steven states quite strongly that

the one recording the IR has the most influence over the resulting music

. This impression is consistent when he records the IR (and I sing through it), and when I record the IR and he plays through it. This may be caused by several things, but of special interest is that it is

diametrically opposed

to what many other performers have stated. Both

Kyle

,

Jordan

and

Kjell

in our initial sessions, voiced a

higher performative intimacy

, a

closer connection

to the output when playing through the IR. Maybe Steven is more concerned with the resulting timbre (including processed sound) than the physical control mechanism, as he routinely designs and performs with his own interactive electronics rig. Of course all musician care about the sound, but perhaps there is a difference of approach on just

how to get there

. With the liveconvolver we put the performers in an unfamiliar situation, and the differences in approach might just show different methods of problems solving to gain control over this situation. What I’m trying to investigate is how the liveconvolver technique works performatively, and in this, the performer’s personal and musical traits plays into the situation quite strongly. Again, we can only observe single occurences and try to extract things that might work well. There is no conclusions to be drawn on a general basis as to what works and what does not, and neither can we conclude what is the nature of this situation and this tool. One way of looking at it (I’m still just guessing) is that Steven treats the convolver as *

the environment

* in which music can be made. The changes to the environment determines what can be played and how that will sound, and thus, the one recording the IR controls the environment and subsequently controls the most important factor in determining the music.

In this session, we also experimented a bit with transposed and revesed IR, this being some of the parametric modifications we can make to the IR with our liveconvolver technique. Transposing can be interesting, but also quite difficult to use musically. Transposing in octave intervals can work nicely, as it will act just as much as a timbral colouring without changing pitch class. A fun fact about reversed IR as used by Steven: If he played in the style of Charlie Parker and we reversed the IR, it would sound like Evan Parker. Then, if he played like Evan Parker and we reversed the IR, it would still sound like Evan Parker. One could say this puts Evan Parker at the top of the convolution-evolutionary-saxophone tree….

Liveconvolver experiment Sax/Vocals, IR recorded by vocals.

Liveconvolver experiment Sax/Vocals, IR recorded by Sax.

Liveconvolver experiment Sax/Vocals, time reversed IR recorded by Sax.

Session with Miller Puckette, May 8th

The session was intended as “calibration run”, to see how the analysis methods responded to Miller’s guitar. This as a preparation for the upcoming bigger session in UCSD Studio A. The main objective was to determine which analysis features would work best as expressive dimensions, find the appropriate ranges, and start looking at potentially useful mappings. After this, we went on to explore the liveconvolver with vocals and guitar as the input signals. Due to the “calibration run” mode of approach, the session was not videotaped. Our comments and discussion was only dimly picked up by the microphones used for processing. Here’s a transcription of some of Millers initial comments on playing with the convolver:

“It is interesting, that …you can control aspects of it but never really control the thing. The person who’s doing the recording is a little bit less on the hook. Because there’s always more of a delay between when you make something and when you hear it coming out [when recording the IR]. The person who is triggering the result is really much more exposed, because that person is in control of the timing. Even though the other person is of course in control of the sonic material and the interior rhythms that happen.”

Since the liveconvolver has been developed and investigated as part of the research on crossadaptive techniques, I had slipped into the habit of calling it a crossadaptive technique. In discussion with Miller, he pointed out that the liveconvolver is not really *crossadaptive* as such. BUT it involves some of the same performative challenges, namely playing something that is not played solely for the purpose of it’s own musical value. The performers will sometimes need to play something that will affect the sound of the other musician in some way. One of the challenges is how to incorporate that thing into the musical narrative, taking care of how it sounds in itself, and exactly how it will affect the other performer’s sound. Playing with liveconvolver has this performative challenge, as has the regular crossadaptive modulation. One thing the live convolver does not have is the reciprocal/two-way modulation, it is more of a one-way process. The recent Oslo session on liveconvolution used two liveconvolvers simultaneously to re-introduce the two-way reciprocal dependency.

Liveconvolver experiment Guitar/Vocals, IR recorded by guitar.

Liveconvolver experiment Guitar/Vocals, IR recorded by guitar.

Liveconvolver experiment Guitar/Vocals, IR recorded by guitar.

Liveconvolver experiment Guitar/Vocals, IR recorded by vocals.

Liveconvolver experiment Guitar/Vocals, IR recorded by vocals.