After an inspiring talk with Marije on March 3rd, I set out to write this blog post to sum up what we had been talking about. As it happens (and has happened before), Marije had a lot of pointer to other related works and writings. Only after I had looked at the material she pointed to, and reflected upon it, did I get around to writing this blog post. So substantial parts of it contains more of a reflection after the conversation, rather than an actual report of what was said directly.

Marije mentiones we have done a lot of work, it is inspiring, solid, looks good.

Agency, focus of attention

One of the first subjects in our conversation was how we relate to the instrument. For performers: How does it work? Does it work? (does it do what we say/think it does?) What do I control? What controls me? when successful it might constitute a

3rd agency

, a shared feeling, mutual control. Not acting as a single musician, but as an ensemble. The same observation can of course be made (when playing) in acoustic ensembles too, but it is connected differently in our setting.

Direct/indirect control

. Play music or generate control signals? Very direct and one-dimensional mappings can easily feel like playing to generate control signals. Some control signals can be formed (by analyzing) over longer time spans, as they represent more of a “situation” than an immediate “snapshot”. Perhaps just as interesting for a musician to outline

a situation over time

, than to simply control one sonic dimension by acting on another?

Out-of-time’d-ness

, relating to the different perceptions of the performative role experienced in IR recording (see posts on convolution sessions

here,

here

and

here

). A similar experience can be identified within other forms of live sampling. to some degree recognizable with all sorts of live processing as an instrumental activity. For the live processing performer: a

detached-ness of control

as opposed to directly playing each event.

Contrived and artificial mappings.

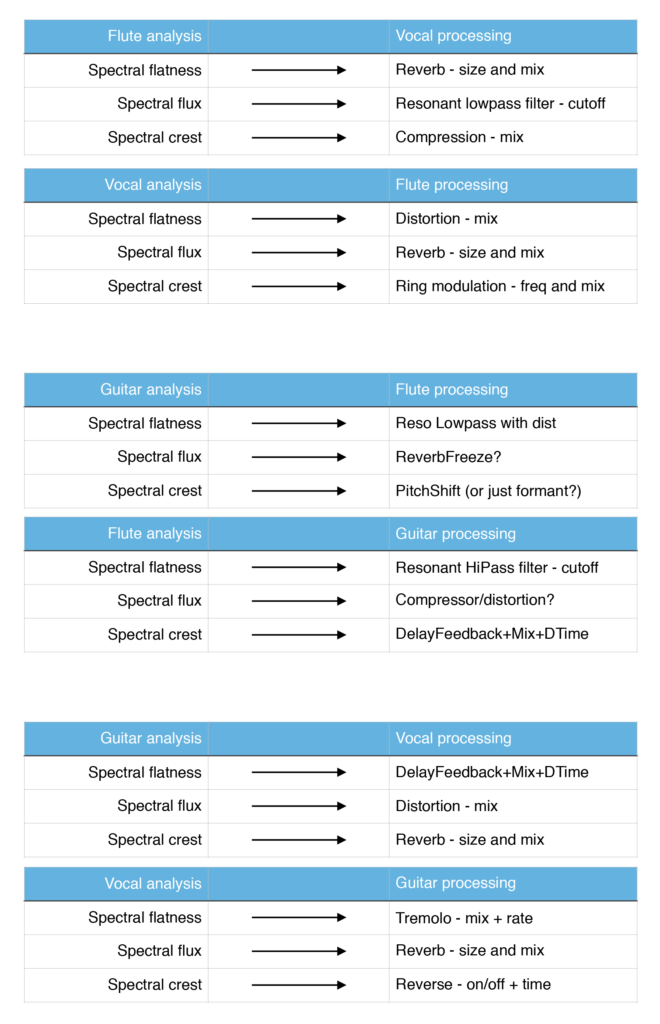

I asked whether the analyzer-modulation mappings are perhaps too contrived, too “made up”? Marije replying that everything we do with electronic music instrument design (and mapping) is to some degree made up. It is always artibrary, design decisions, something made up. There is not one “real” way, no physical necessity or limitation that determines what the “correct” mapping is. As such, there are only mappings that emphasize different aspects of performance and interaction, new ideas that might seem “contrived” can contain yet-to-be-seen areas of such emphasis.

Composition

is in these connections. For longer pieces one might want variation in mapping. For example, in the combined instrument created by voice and drums in some of our research sessions. Depending on combination and how it is played, the mapping might wear out over time, so one might want to change it during one musical piece.

Limitation.

In January I did a presentation at UC Irvine, for an audience well trained in live processing and electronic music performance. One of the perspectives mentioned there was that the cross-adaptive mapping could also be viewed as a limitation. One could claim that all of these modulations that we can perform cross-adaptively could have been manually controlled, an with much more musical freedom if manually controlled. Still, the crossadaptive situation provides

another kind of dynamic

. The acoustic instrument is immediate and multidimensional, providing a nuanced and intuitive interface. We can tap into that. As an example as to how the interfacne changes the expression, look at how we (Marije) use accelerometers over 3 axes of motion: one could produce the same exact same control signals using 3 separate faders, but the

agency of control

, the feeling, the expressivity, the dynamic is different with accelerometers that it is with faders. It is

different to play

, and this will produce different results. The limitations (of an interface or a mapping) can be viewed as something interesting, just as much as something that inhibits.

Analyzer noise and flakyness

One thing that have concerned me lately is the fact that the analyzer is sometimes too sensitive to minor variations in the signal.

Mathematical differences

sometimes occur on a different scale than the

expressive differences

. One example is the rhythm analyzer, the way I think it is too noisy and unreliable, seen in the light of the practical use in

session

, where the musicians found it very appropriate and controllable.

Marije reminds me that in the live performance setting,

small accidents and surprises

are inspiring. In a production setting perhaps not so much. Musicians are trained to

embrace the imperfections

of, and

characteristic traits

of their instument, so it is natural for them to also respond in a similar manner to imperfections in the adaptive and crossadaptive control methods. This makes me reflect if there is a research methodology of accidents(?), on how to understand the art of the accident, understand the failure of the algorithm, like in glitch, circuit bending, and other art forms relating to distilling and refining “the unwanted”.

Rhythm analysis

I will refine the rhythm analysis, it seems promising as a measure

of musical expressivity. I have some ideas of maintaining several parallel hypotheses on how to interpret input, based on previous rhythm research. some of this comes from “Machine Musicianship” by Robert Rowe, some from readin a UCSD dissertation by Michelle L. Daniels: “An Ensemble Framework for Real-Time Beat Tracking”. I am currently trying to distill these into a simplest possible method of rhythm analysis for our purposes. So I ask Marije on ideas on how to refine the rhythm analyzer. Rhythm can be one parameters that outlines “a situation” just as much as it creates a “snapshot” (recall the discussion of agency and direct/indirect control, above). One thing we may want to extract is slower shifts, from one situation to another. My concerns that it takes

too long

to analyze a pattern (well, at least as long as the pattern itself, which might be several seconds) can then be regarded less of a concern, since we are not primarily looking for immediate output. Still, I will attempt to minimize the latency of rhythm analysis, so that any delay in response is due to aestethic choice, and not so much limited by the technology. She also mentions the other Nick Collins. I realize that he’s the one behind the bbcut algorithm also found in Csound. I’ve used a lot a long time ago. Collins has written a library for feature extraction within SuperCollider. To some degree there is overlap with feature extraction on our Analyzer plugin. Collins invokes external programs to produce

similarity matrices

, something that might be useful for our purposes as well, as a means of finding temporal patterns in the input. In terms of rhythm analysis, it is based on beat tracking as is common. While we in our rhythm analysis attempts at *not relying* on beat tracking, we could still perhaps implement it, if nothing else so to use it as a measure of beat tracking confidence (assuming this as a very coarse distinction between beat based and more temporally free music.

Another perspective on rhythm analysis can also perhaps be gained from Clarence Barlow’s interest in ratios.

The ratio book

is available online, as is a lot of his

other writings

. Barlow states “In the case of ametric music, all pulses are equally probable”… which leads me to think that any sort of statistical analysis, frequency of occurence of observed inter-onset times, will start to give indications of “what this is”… to lift it slowly out of the white-noise mud of equal probabilities.

Barlow uses the “

Indispensability formula

“, for relating the importance of each subdivision within a given meter. Perhaps we could invert this somehow to give a general measure of “

subdivided-ness

“?. We’re not really interested in finding the meter, but the

patterns of subdivision

is nonetheless of interest. He also use the “

Indigestibility formula

” for ratios, based on prime-ness, suggests also a cultural digestability limit around 10 (10:11, 11:12, 12:13 …). I’ve been pondering different ways of ordering the complexity of different integer ratios, such as different trhythmic subdivisions. The indigesibility formula might be one way to approach it, but reading further in the ratio book, the writing of Demetrios E. Lekkas leads me to think of

another way to sort the subdivisions into increasing complexity:

Lekkas describes the traditional manner of writing down all rational numbers by starting with 1/1 (p 38), then increasing the numerator by one, then going through all denominators from 1 up to the nominator, skipping fracions that can be simplified since they represent numbers earlier represented. This ordering does not imply any relation to complexity of the ratios produced. If tried to use it as such, one problem with this ordering is that it determines that subdividing in 3 is less complex than subdividing in 4. Intuitively, I’d say a rhythmic subdivision in 3 is more complex than a further subdivision of the first established subdivision in 2. Now, could we, to try to find a measure of complexity, assume that

divisions further apart from any previous established subdivision

are

simpler

than the ones creating closely spaced divisions(?). So, when dividing 1/1 in 2, we get a value at 0.5 (in addition to 0.0 and 1.0, which we omit for brevity). Then, trying to decide what is the next further division is the most complex, we try out all possible further subdivision up to some limit, look at the resulting values and their distances to already excisting values.

Dividing in 3 give 0.33 and 0.66 (approx), while dividing in 4 give the (new) values 0.25 and 0.75. Dividing by 5 gives new values at .2 and .4, by 6 is unnecessary as it does not produce any larger distances than already covered by 3. Divide by 7 gives values at .142, 0.285 and .428. Divide by 8 is unnecessary as it does not produce any values of larger distance than the divide by 4.

The lowest distance introduced by dividing in 3 is 0.33 to 0.5, a distance of approx 0.17. The lowest distance introduced by dividing in 4 is from 0.25 to 0.5, a distance of 0.25. Dividing into 4 is thus less complex. Checking the divide by 5 and 7 can be left as an exercise to the reader.

Then we go on to the next subdivision, as we now have a grid of 1/2 plus 1/4, with values at 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75. The next two alternatives (in increasing numeric order) is division by 3 or division by 5. Division by 3 gives a smallest distance (to our current grid) from 0.25 to 0.33 = 0.08. Division by 5 gives a smallest distance from 0.2 to 0.25 = 0.05. We conclude that division by 3 is less complex. But wait, let’s check division by 8 too while we’re at it also here, leaving divide by 6 and 7 as an exercise to the reader). Division by 8, in relation to our current grid (.25, .5, .75) gives a smallest distance of 0.125. This is larger than the smallest distance produced by division in 3 (0.08), so we choose 8 as our next number in increasing order of complexity.

Following up on this method, using a highest subdivision of 8, eventually gives us this order 2,4,8,3,6,5,7 as subdivisions in increasing order of complexity. This

coincides with my intuition of rhythmic complexity

, and can be reached by the simple procedure outlined above. We could also use the same procedure to determine the exact value of complexity for each of these subdivisions, as a means to create an output “value of complexity” for integer ratios.

As a side note to myself, check how this will differ from using Tenney height or Benedetti height as I’ve used earlier in the Analyzer.

On the justification for coming up with this procedure I might lean lightly on Lekkas again: “If you want to compare them you just have to come up with your own intuitive formula…deciding which one is more important…That would not be mathematical. Mind you, it’s non-mathematical, but not wrong.” (Ratio book p 40)

Much of the book relates to

ratios as in pitch ratios and tuning

. Even though we can view

pitch and rhythm

as activity within the same scale, as vibrations/activations at different frequencies, the perception of pitch is further

complicated by the anatomy of our inner ear

(critical bands), and by

cultural aspects and habituation

. Assumedly, these additional considerations should not be used to infer complexity of rhythmic activity. We can not directly use

harmonicity of pitch

as a measure of the

harmonicity of rhythm

, even though it might *to some extent* hold true (and I have used this measure up until now in the Analyzer).

Further writings by Barlow on this subject can also be found in his

On Musiquantics

. “Can the simplicity of a ratio be expressed quantitatively?” (s 38), related to the indegestability formula. See also how “metric field strength” (p 44), relates to the indispensability formula. The section from p 38-47 concerns this issue, as well as his “Formulæ for Harmonicity” p 24, (part II), with Interval Size, Ratios and Harmonic Intensity on the following pages. For pitch, the critical bandwidth (p 48) is relevant but we could discuss if not the “larger distance created by a subdivision” as I outlined above is more appropriate for rhythmic ratios.

Instrumentality

The 3Dmin book “

Musical Instruments in the 21st Century

” explores various notions of what an instrument can be, for example the instrument as

a possibility space

. Lopes/Hoelzl/de Campo, in their many-fest “favour variety and surprise over logical continuation” and “enjoy the moment we lose control and gain influence”. We can relate this to our recent reflections on how performers in our project thrive in a setting where the analysis meethods are somewhat noisy and chaotic. The essence being they can

control the general trend of modulation

, but still be surprised and disturbed” by the immediate details. Here we again encounter methods of the “less controllable”: circuit bending, glitch, autopoietic (self-modulating) instruments, meta-control techniques (de Campo), and similarly the XY interface for our own Hadron synthesizer, to mention a few apparent directions. The 3DMIN book also has a chapter by Daphna Naphtali on using

live processing as an instrument

. She identifies some potential problems about the

invisible instrument

. One problem, according to Naptali, is that it can be difficult to identify the contribution (of the performer operating it). One could argue that invisibility is not necessarily a problem(?), but indeed it (invisibility and the intangible) is a

characteristic trait

of the kind of instruments that we are dealing with, be it for live processing as controlled by an electronnic musician, or for crossadaptive processing as controlled by the acoustic musicians.

Marije also has a chapter in this book, on the blurring boundaries between composition, instrument design, and improvisation. …”the algorithm for the translation of sensor data into music control data is a major artistic

area; the definition of these relationships is part of the composition of a piece”

Waisvisz 1999

, cited by Marije

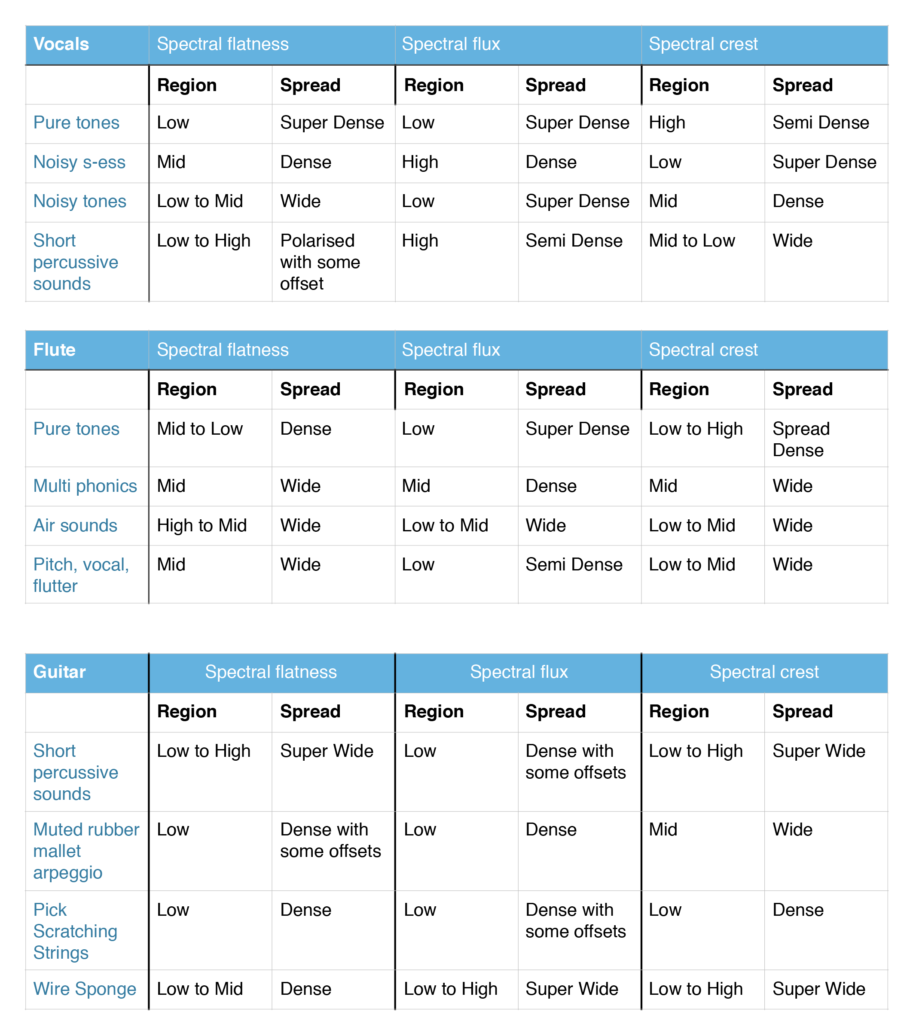

Using adaptive effects as a learning strategy

In light of the complexity of crossadaptive effects, the simpler adaptive effects could be used as a means of familiarization for both performers and “mapping designers” alike. Getting to know how the analyzer reacts to different source material, and how to map the signals in a musically effective manner. The adaptive use case is also more easily adaptable to a mixing situation, for composed music, and any other kind of repeatable situation. The analyzer methods can be calibrated and tuned more easily for each specific source instrument. Perhaps we could also look at a

possible methodology for familiarization

, how do we most efficiently learn to know these feature-to-modulator mappings. Revising the literature on adaptive audio effects (Verfaille etc) in the light of our current status and reflections might be a good idea.

Performers utilizing adaptive control

Similarly, it might be a good idea to get on touch with environments and performers using adaptive techniques as part of their setup. Marije reminded me that Jos Zwaanenburg and his students at the Conservatorium of Amsterdam might have more examples of musicians using adaptive control techniques. I met Jos some years ago, and contacted him again via email now.

Hans Leeouw

is another Dutch performer working with adaptive control techniques. His 2009 NIME article mentions no adaptive control, but has a beautiful statement on the design of mappings: “…when the connection between controller and sound is too obvious the experience of ‘hearing what you see’ easily becomes ‘cheesy’ and ‘shallow’. One of the beauties of acoustic music is hearing and seeing the mastery of a skilled instrumentalist in controlling an instrument that has inherent chaotic behaviour “. In the 2012 NIME article he mentions audio analyses for control. I Contacted Hans to get more details and updated information about what he is using. Via email he tells that he use noise/sinusoidal balance as a control both for signal routing (trumpet sound routed to different filters), and also to reconfigure the mapping of his controllers (as appropriate for the different filter configuration). He mentions that the analyzed transition from noise to sinusoidal can be sharp, and that additional filtering is needed to geet a smooth transition. A particularly interesting area occurs when the routing and mapping is in this intermediate area, where both modes of processing and mapping are partly in effect.

As an example of on researcher/performer that has explored voice control, Marije mentioned

Dan Stowell

.

Nor surprisingly, he’s also done his research in the context of QMUL. Browsing his thesis, I note some useful terms for ranking extracted features, as he writes about *

perceptual relevance

*, *

robustness

*, and *

independence

*. His experiments on ranking the different features are not conclusive, as “none of the experiments in themselves will suggest a specific compact feature set”. This indication coincides with our own experience so far as well, that different instruments and different applications require different subsets of features. He does however mention

spectral centroid, to be particularly useful

. We have initially not used this so much due to a high degree of temporal fluctuation. Similarly, he mentions

spectral spread

, where we have so far used more

spectral flatness

and

spectral flux

. This also reminds me of recent discussions on the Csound list regarding

different implementations of the analysis of spectral flux

(difference from frame to frame or normalized inverse correlation), it might be a good idea to test the different implementations to see if we can have several variations on this measure, since we have found it useful in some but not all of our application areas. Stowell also mentions

log attack time

, which we should revisit and see how we can apply or reformulate to fit our use cases. A measure that we haven’t considered so far is

delta MFCCs

, the temporal variation within each cepstral band. Intuitively it seems to me this couldd be an alternative to spectral flux, even though Stowell have found it not to have a significant mutual information bit (delta MFCC to spectral flux). In fact the Delta MFCCs have little MI with any other features whatsoever, although this could be related to implementation detail (decorrelation). He also finds that Delta MFCC have low robustness, but we should try implementing it and see what it give us. Finally, he also mentions *

clarity

* as a spectral measure, in connectino to pitch analysis, defined as “

the normalised strength of the second peak of the autocorrelation trace

[McLeod and Wyvill, 2005]”. It is deemed a quite robust measure, and we could most probably implement this with ease and test it.